Welcome to the blog highlighting the website ‘Beresford’s Lost Villages’ and the material that can be found there, continuing the review of the counties were it has been possible to provide full descriptions of all deserted villages listed in the Gazetteer of settlements in 1968. This week we look at two northern counties that were both highlighted in 1971 as needing further local research to provide a real picture of the nature of deserted settlement in the area – Cheshire and Cumberland (Beresford and Hurst 1971).

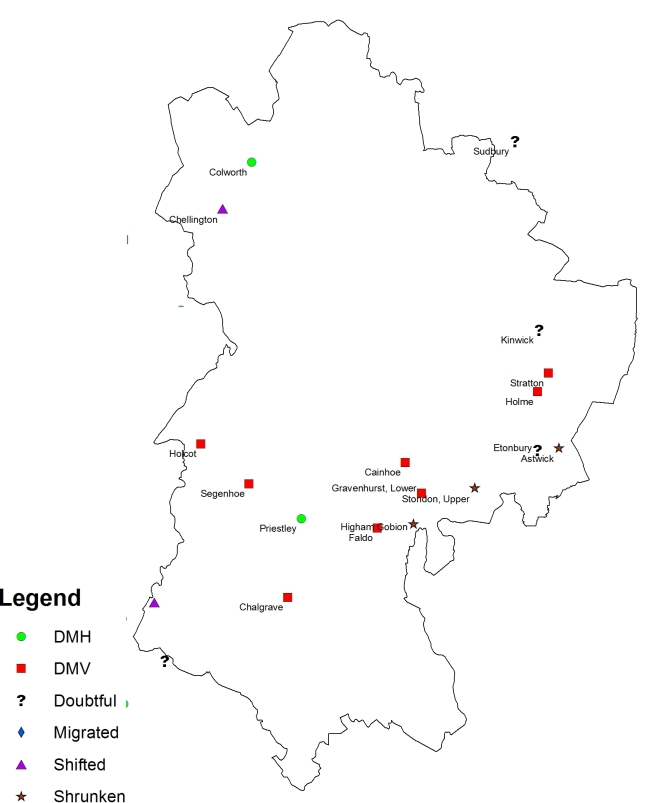

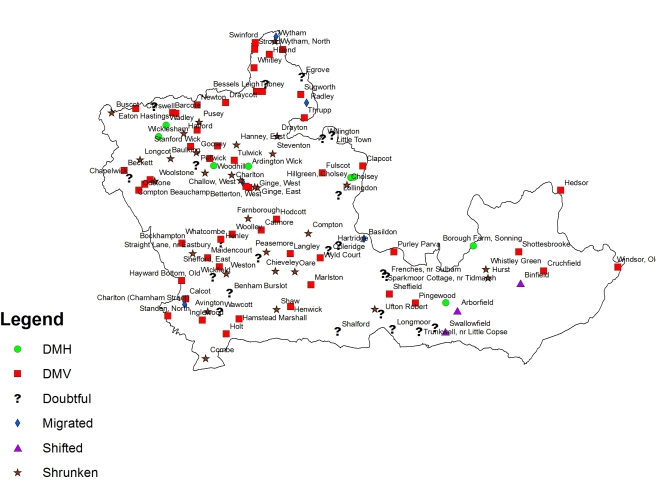

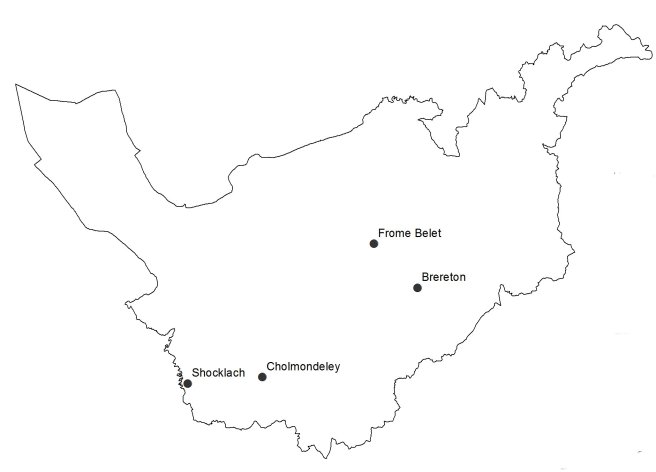

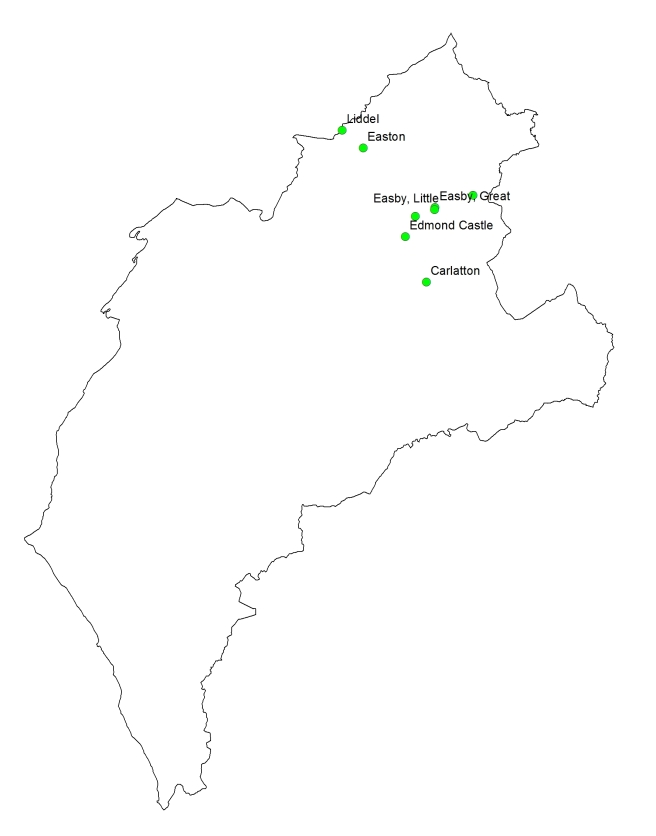

Only four settlements in Cheshire and eight settlements in Cumberland appear in the 1968 Gazetteer. In both counties there is also a clustering of sites into regions where some fieldwork had been undertaken. For Cumberland it is a little confusing why some of the earlier work in the county had not been used when compiling the list. For example in 1963 William Rollinson published a paper entitled ‘The lost villages and hamlets of Low Furness’ (Rollinson 1963). This suggested at least five lost settlements in this one small area. It also explored theories from the 1770s onwards as to why these settlements disappeared including tidal inundations and monastic developments.

Since 1968 a number of surveys have taken place as well as a consideration of the nature of settlement in these counties during the medieval period. In 1975 the MVRG noted that over the last four years much work had been undertaken on Cheshire with the documentary sources but that fieldwork needed to be done (Dyer 1975). Work by a number of individuals including D. Sylvester had noted the dispersed nature of settlement in a number of townships (Dyer 1975). It is now clear that this is a much more widespread pattern and that Cheshire as a whole had a great deal of dispersed settlement so the exact nature of the village and settlement make-up is difficult to reconstruct. Many of the settlements that become classed as deserted may not have been large nucleated entities in the first place. Many townships by the nineteenth century still contained no nucleated settlements (Edwards 2007). The main concentration of nucleated settlement in Cheshire is located to the west of the central Cheshire ridge (Dyer 1975).

A similar pattern can be seen in Cumberland. With many of the sites identified in Cumberland it is questionable whether there was ever extensive nucleated settlement at these locations. The documentary record is patchy, but those settlements with records seem to have declined in the fourteenth century. Analysis of the general settlement pattern over much of Cumbria has also highlighted the high percentage of dispersed settlements consisting of single farmsteads or a couple of dwellings (Newman 2006, 2009). The landscape of the area is varied though and in some areas classical nucleated settlement can also be found. This pattern seems to have a long history. Not only does this make understanding the true pattern of desertion across the county difficult, there is also the issue that it can be difficult to identify medieval dispersed settlement as they are ‘more easily rendered ‘invisible’ by later land use’ (Newman 2006: 121). The Research Agenda for the North West has prioritised the investigation of evolution of dispersed settlement and to investigate the ways settlement expanded into marginal areas in the Medieval period (Newman and Newman 2007).

With this dispersed nature of settlement in both counties, it has led to many of the settlements listed in 1968 being now classed as doubtful deserted medieval settlements as it is unclear whether a nucleated settlement ever existed at that location. One of the key challenges with these regions is the patchy existence of medieval taxation documentation – often key to plotting the existence and development of medieval populations.

The palatine of Cheshire was exempt from most medieval taxation so few records appear after the Domesday Book until the sixteenth century. Cumberland in some periods belongs to Scotland, at other times it is exempt from taxation due to Scottish raids and troubles. Cumberland was not recorded in the Domesday Book, however a small number of places are recorded in the Domesday record for Yorkshire, but this is limited to just four places (Faull and Stinson 1986). In 1334 there is no Lay Subsidy for Cheshire and for Cumberland there was no tax due to recent devastation by the Scots so Glasscock (in his publication of the Lay Subsidy) has substituted this with the 1336 tax figures allowing some indication of the presence of settlements (Glasscock 1975: xxiii). It is suggested that due to ongoing devastation from the Scots the payments are probably low (Glasscock 1975: 36). In 1377 no writ was issued for the Poll Tax in Cheshire. In 1379 commissions were supposed to levy the tax, but this was cancelled and they were asked for an offer of aid instead (Fenwick 1998: xxi). The Crown confirmed Cheshire’s immunity from parliamentary taxation in 1381 (Fenwick 1998: xxi). Although Cumberland was taxed in the fourteenth century there has been limited survival of the documents for the whole of Cumberland. Only one nominative list has survived from the 1377 Poll Tax (Fenwick 1998: 90). While this membrane is in good condition, it refers solely to Carlisle and does not refer to any of the deserted settlements. There are no surviving records for 1379 or 1381. Again in the sixteenth century no Lay Subsidy was required in 1524, 1525 or 1543 for both counties (Sheail 1998: 3).

Overall these two counties are representative of a situation outside the main ‘planned’ landscapes of central England. The nature of dispersed settlement, but also very variable local settlement patterns, results in a different type of challenge when trying to evaluate the extent and nature of settlement desertion. Much work has already been done tackling these regions and it is anticipated that once the Beresford’s Lost Villages Website Project moves into the next phase of updating the 1968 county lists, that these two counties will see a dramatic increase in the number of settlements recorded – although the number of ‘nucleated’ settlements may be limited and more evidence of deserted hamlets may well be apparent.

References

Beresford, M.W. and J.G. Hurst (eds) 1971. Deserted Medieval Villages: Studies. London: Lutterworth Press.

Dyer, C. 1975. ‘Research in 1975: Cheshire’, Medieval Village Research Group Report 23: 7-10.

Edwards, R. 2007. The Cheshire Historic Landscape Characterisation Final Report. Cheshire County Council & English Heritage Unpublished Report.

Faull, M.L. and M. Stinson 1986. Domesday Book: Yorkshire Part Two. Chichester: Phillimore.

Fenwick, C.C. 1998. The Poll Taxes of 1377, 1379 and 1381: Part 1: Bedfordshire-Leicestershire. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Glasscock, R.E. 1975. The Lay Subsidy of 1334. London: Oxford University Press.

Newman, C. 2006. ‘The Medieval Period Resource Assessment’, Archaeology North West 8: 115-144.

Newman, C. and R. Newman 2007. ‘The Medieval Period Research Agenda’, Archaeology North West 9: 95-114.

Newman, R. 2009. A Guide to Using the Cumbria Historic Landscape Characterisation Database For Cumbria’s Planning Authorities. Cumbria County Council Unpublished Report.

Rollinson, W. 1963. ‘The Lost Villages and Hamlets of Low Furness’, Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society 63: 160-169.

Sheail, J. 1998. The Regional Distribution of Wealth in England as Indicated in the 1524/5 Lay Subsidy Returns: Volume One. London: List and Index Society.